WV Remembers is pleased to provide a reprint of Mannix Porterfield’s October 19, 1996 article about Max Lewin and his Holocaust experience.

To Hell & Back

Max Lewin survived the inhumanity of the Holocaust, but the former resident of Poland can never forget the horrors.

By Mannix Porterfield REGISTER-HERALD REPORTER

Until the soldiers came, life for young Max Lewin in his native Poland seemed idyllic. In a cozy house overlooking I00 placid acres of farmland in Lipinski, he shared chores with three brothers and three sisters.

“My father was a little bit of everything,” Lewin said. “He was a real estate man. People who had maybe 2,000 or 5,000 acres and wanted to sell something, they would give money to parcel it out. He was a speculator.”

His father’s side of the family engaged in business of one kind or another, while his mother came from a long line of rabbis. She hoped young Max would follow them. He was born Sept. 20, just before Yom Kippur.

“I was not very religious, although I was in a very religious home,” he said. “Everything was kosher.”

Life was traditional for a middle-class Jewish family of the period – the mother, Sarah, tended to rearing the children, while father Yechiel earned a living.

The Lewins owned cows and horses and grew enough crops to maintain a healthy diet, one that helped steel young Max for the horrors of German occupation of Europe in World War II.

Besides Max, there were brothers Harry, Awner and Joseph, and sisters Hannah, Leah and Chaia. When he was a lad of 12 or so, young Max got a bicycle. Before that, a horse-drawn buggy served as the family’s sole means of transportation.

Little Max – actually Meyer was his first name, borrowed from a grandfather – soon became a familiar sight, pedaling the bicycle across town.

“We were so happy,” he said, breaking into a smile. “We had a close-knit family. Mother was boss. But I honestly don’t ever recall being spanked. We were good boys.”

Across Europe, however, a sinister force was rearing its head in Germany, yet reeling in the economic aftershocks of World War I. Angry men in brown shirts emblazoned with swastikas knifed the air with stiff-arm salutes in the shadows of torchlight rallies. Jewish business owners were harassed. Street brawls erupted in the villages. Books were burned.

And in the midst of all this insanity, a bizarre little man with a Charlie Chaplin mustache, Adolf Hitler, was plotting to capture the world for fascism.

In Poland, no one seemed to understand the upheaval in Germany.

“Nobody knew what was going on,” Lewin said. “Nobody believed it.” But in Israel, brother Awner sensed impending doom for his brethren and wrote letters urging his father to get the family out of Poland.

“Europe is a fire,” he wrote. “Go! Run!”

“I didn’t read his letters because I wasn’t interested in them,” Max Lewin said.

“I was just a kid. I remember he was telling them to ‘Go.’ But you couldn’t tell it to my father. He was so tied up in the life that he had. He just couldn’t believe it. Nobody could believe it.”

Reality arrived Sept. 1, 1939, in the form of shock troops, when the Germans invaded his homeland, officially setting World War II in motion. At the time, Russian troops were still in Poland. To Lewin and his fellow Jews, there was little difference.

“The Russians were always tough on the Jewish people.”

At age 19, Max found himself drafted by the battered Polish army. His military career with the Poles lasted only three days. By then, Poland was a defeated nation. Max was sent home with a buddy.

His bride-to-be, Fruma, found him with a close-cropped haircut, a tradition with which raw recruits in the U.S. military are familiar.

Young Max then found himself in demand by the Russian Army, but that also was a brief fling, lasting about four or five days.

German troops poured into his hometown and confiscated anything of value in the Lewin household, leaving the family live in one room in the back. m «They took our house and made it into a warehouse,” he said. “They were loading up trucks and backing them in. It was just like a warehouse. The Russians didn’t stay long. Germany took over.

“First thing they did was take out everything, whatever you had.”

Soup lines snaked across the besieged town. Citizens were forced to ration food and other goods.

As the new order took hold, the occupying Germans followed a tactic employed in other nations – muscling in to manipulate a local Jewish self-help group, forged as a defensive move in response to centuries of fierce anti-Semitism. In Poland, the group was known as Judenrat.

Six months after his town was taken over, Lewin found himself being herded 14 kilometers away with family and friends to a ghetto known as Iwja. Four families piled into one house.

“All the Jews were brought into this one community,” he said.

Lewin and his father were sent to work in a sawmill under the watchful eyes of German troops. Before long, farmers picked the experienced Max to help them.

This lasted for about six months. And then came a sickening and horrific change in German policy toward Polish Jews.

On a warm Sunday night in summer, the Holocaust began in earnest. Word was sent by the Judenrat that their captors wanted 100 strong, young men with shovels to fall out into a parking lot for inspections.

“We didn’t know what was going on,” he said. “We thought maybe we were going to dig something.”

For three miles, the puzzled young men, each toting a spade, walked along a road until they came upon a rectangle chalked on the ground. It was roughly the length of a football field and about 60 feet wide.

Holding machine pistols at arm’s length, the Germans barked out orders to start digging. The excavation went down 4 feet in the soft turf.

“We still didn’t know anything about it,” he said.

Really, all the young men knew was that the wanted this task done quickly. The job took about four hours.

German soldiers kept them at a torrid pace, yelling, “Schnell! Schnell machen!”

“It was just about the way it is now,” Lewin said recently, looking out a window at the gathering dusk of twilight. “They came over and looked it over, and straightened it out here, and straightened it out there, you know.

“And there was no argument. You did whatever they said. Otherwise, they shot you.”

Back in town, a rising sense of foreboding spread among the older people. Their worst nightmares were about to be realized.

“My father used to tell me that time heals all wounds. But for me, it hasn’t.” MAX LEWIN, Holocaust survivor

“That was the beginning,” Lewin said. “That was when the trouble started.”

When morning dawned, the ghetto dwellers were ordered to be dressed and in the street. Around I0 a.m., tanks rumbled in, followed by heavy trucks filled with grim-faced troops.

“Then we got scared,” Lewin said.

A slight man, obviously in charge, paced back and forth, making his selections until he had chosen 7,000 victims. Systematical and clinical was the German method of extermination. All the Jews chosen to die were ordered to stack jewelry, clothes and footwear in neat piles.

Lewin and his family had been spared, for the moment, only to suffer the agonizing sound of others falling under volleys of machine-gun fire. Afterward, young Max and his shovelers were compelled to spread lime and dirt over the victims, many of them still alive and shrieking in pain.

Families were decimated in that 1941 [Ed. Note May 12, 1942] slaughter. Four months later, what remained of the Jews, including the Lewin family, were herded into another ghetto, Borisov, where a curfew was enforced rigidly.

“There, you knew you were a prisoner,” he said.

The German death merchants accelerated their merciless campaign against the Jews, and this time, in a mass killing on March 10, 1943, the young Lewin lost most of his family, including his wife.

All that remained with him were the youngest boy, Joseph, and an older sister. Why those three were spared, only the Germans knew, and they were not accustomed to saying why.

“They backed up with big trucks and picked up the people like cattle,” he recalled through tears. “Then somebody else pulls up and does something in a wooded area. You could hear the machine guns going.

“There were very few of us left then.”

From there the painful odyssey stretched into the Minsk labor camp, where the rigors of concentration life soon claimed his only surviving sister.

“She was so little and so sick,” Lewin sobbed. [Ed. Note: this differs from Max’s 1968 account which had Leah dying at Treblinka].

“My brother was sick, but he made it. And I made it. My sister didn’t. “We didn’t have any place to go. You go into Russian hands, and you were dead. You go into German hands, you were dead.”

Once this abomination was etched into Holocaust history, the two Lewin brothers found themselves across the German border at a concentration camp in Lublin. By now, the German approach to genocide had become more sophisticated. Gas chambers replaced the mass killings of the outdoors.

All from the Polish hometown clung together like family. Once the boxcars delivered their human cargo, however, separation would come. The man in charge began dividing the captive Jews into two lines. Fate put the brothers in opposing flanks.

“He went left, and I went right,” Lewin said.

“That was the end of it. All the counting he did. He could have counted this way and that way. I couldn’t run after him. If you did, they’d kick you. You couldn’t do anything. Once they counted you, that was it.”

In the rush of Jews numbering some 10,000 marching off to another Nazi-built hellhole, young Joseph and Max looked upon each other for the last time.

Even in the midst of such boundless and irrational hatred, Lewin can recall fragments of tenderness. He found proof that the Nazis had not squeezed out every drop of human kindness from the German people.

An old woman, leading an oxen-pulled cart, lost two sons to Hitler’s war machine. In sympathy, she sneaked scraps of bread and potatoes to the Poles.

Lewin, all alone now, passed through a succession of concentration camps – names that are forever etched in his memory. Auschwitz. Natzweiler-Struthof. Dachau. Neckarlez.

In a panic, the Germans furiously sought to cover their tracks with the Allies pressing closer. Almost every night, in the final days of his captivity, Lewin heard planes blasting the German towns.

“We didn’t know who was fighting,” he said. “It didn’t make any difference. We weren’t human.”

Led out of a long tunnel, Lewin found some 20 women American Red Cross uniforms but no American troops. Starved for so long, many of the camp occupants tore into deserted German homes to raid food boxes and cellars, only to overtax their emaciated frames.

“How many people lived three and a half, four years in German camps, and they died when their freedom came,” Lewin sighed.

“They were so hungry and thirsty. So, they overdid it and died right there.”

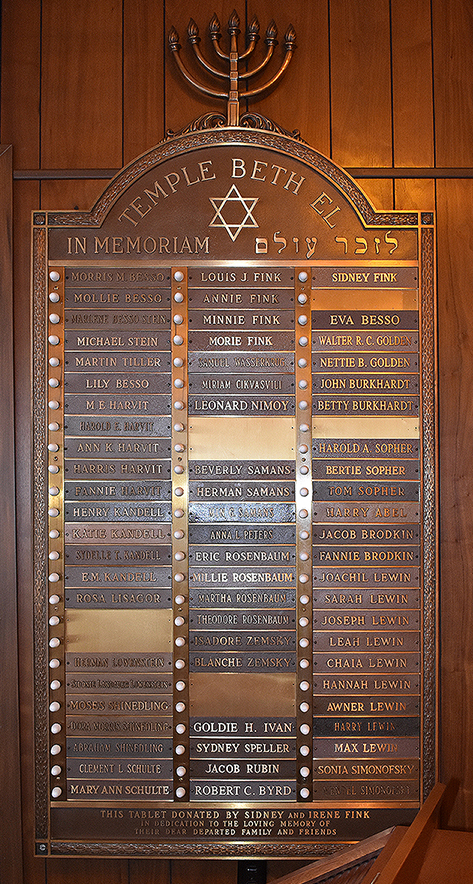

Lewin arrived in the United States on May 26, 1946, and soon joined his brother Harry, who came to the United States before the war, in running a men’s clothing store in Beckley.

Exactly two decades ago, Lewin visited Israel and paid a return visit to Germany.

In a small town, old fears were revived when he found a government-built synagogue in which to worship. Immediately after the service ended, the worshippers rushed out and the lights clicked off, leaving Lewin alone and puzzled inside.

“We are afraid to go out at night,” a rabbi confided in him. “There are so many Nazis here.”

The episode read like a chapter out of “The Odessa File.”

Even so, Lewin is convinced that the world learned a mighty, if burdensome, lesson from the Holocaust. And that lesson is simply that it should not be repeated.

“You lived from day to day,” the amiable Holocaust survivor related. “You never knew if you were going to be alive the next day or dead. I don’t see how humans can do things like that.

“Yet, I was there, and I just couldn’t believe it. There is just no explanation to it. Look at Hitler. He died like a dog. They covered him with gasoline and burned him. And he asked for it.

“And what did he accomplish?”

Lewin says he harbors no hatred for the German people. He recalled Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthall’s encounter with a dying soldier, who begged his forgiveness.

“The Jewish people are supposed to forgive,” he said. “You can’t blame all the Germans for what happened. I believe the world learned. I believe Germany learned.”

For Max Lewin, the lessons of hate and genocide can never be expunged.

“My father used to tell me that time heals all wounds,” he said, weeping into his hands. “But for me, it hasn’t.”

Temple Beth El invites you to attend the Beckley Annual Holocaust Remembrance Day on April 15, 2018 at WVU Tech’s Carter Hall. The program will begin at 1:00 PM.